Minamata Bay in Japan: How One Factory Ruined Thousands of Lives

Ethan Lee ’25

Daphne Wong ’26

It is the year 1956. A cat roams the busy streets of Minamata, passing by an endless series of vendors selling various types of seafood. For the people of this small seaside city, it is a typical day; for the cat, however, it is its last. People stop and watch as the cat stumbles around the street, its back two legs seemingly paralyzed; it frequently bumps into a person or trips over the curb. Later that night, the cat finally collapses. Locals (ironically) termed this behavior “dancing cat fever.” At the time, many animals were facing their demise similarly; cats dropped dead or fell into the bay, birds fell out of the sky, and dead fish floated in the sea. Unbeknownst to the inhabitants of Minamata, they too would be affected by this strange condition, which would later be known as the Minamata disease.

Hideo Ikoma was fifteen when he started to experience symptoms of Minamata disease. After waking up from a nap one day, his mouth was numb. When he tried to call for his father, nothing came out except for incoherent fragments of speech. The disease had dealt severe damage to his Central Nervous System (CNS), leading to a loss of feeling in the mouth and other extremities. But the problems did not stop there. At the age of 74 – approximately 60 years later – Hideo still grapples with the complications of a damaged CNS, including ataxia, slurred speech, vision loss, hearing loss, and cognitive impairment, among other issues. Many victims were not as lucky and died soon after contracting the disease. Unfortunately, the disease has no cure – patients must take medicine to mitigate their symptoms individually (JSTOR, 2018).

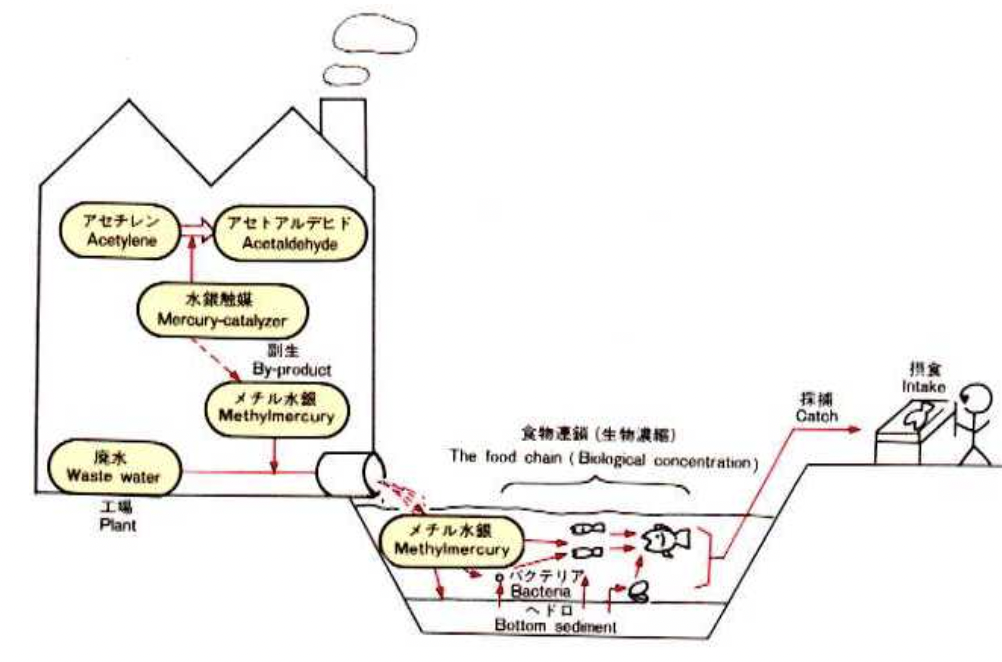

To understand how Minamata disease made its way into the bodies of humans, one must first learn more about the situation of Minamata and its inhabitants. Given its proximity to the sea, the city’s staple foods were fish and shellfish. In 1908, the Chisso Corporation opened a chemical factory in Minamata, Kumamoto Prefecture (prefectures are vaguely similar to states or provinces). The factory started producing fertilizers and eventually branched out to produce acetylene, acetaldehyde, acetic acid, vinyl chloride, octanol, and other chemicals for commercial use. The Chisso factory was the most advanced in Japan – even after World War 2 – and employed approximately 60% of the local workforce in the 1950s and 1960s. Needless to say, it brought economic prosperity to Minamata and its people. However, this economic prosperity did not come without consequences (Wikipedia, 2024).

The factory started producing acetaldehyde in 1932, and in 1960, production peaked at roughly 45,000 tons. To put this into perspective, the factory yielded between a quarter and a third of Japan’s total acetaldehyde. Mercury sulfate – inorganic mercury – was used to catalyze the acetaldehyde chemical reaction. A side reaction of this catalytic cycle produced methylmercury, a type of organic mercury. This form of mercury resulted in many consequences for the people of Minamata.

Between 1932 and 1968, the factory released approximately 600 tons of mercury into Minamata Bay as wastewater. Wastewater is aqueous discard from manufacturing processes like that of acetaldehyde. Most of this mercury came in the form of methylmercury or mercury sulfate. Usually, inorganic mercury (mercury sulfate, in this case) is not as readily absorbed by fish and other organisms. However, much of the mercury sulfate discharged into the bay was converted to methylmercury by anaerobic bacteria found in the bay’s sediment. Since methylmercury is organic, it is consumed by plankton and plants, which are consumed by larger organisms. Eventually, this methylmercury made its way into fish and shellfish – the staple foods of Minamata – and onto the plates of humans. Birds and cats, which relied on fish as their primary food source, were also poisoned by methylmercury (JSTOR, 2018).

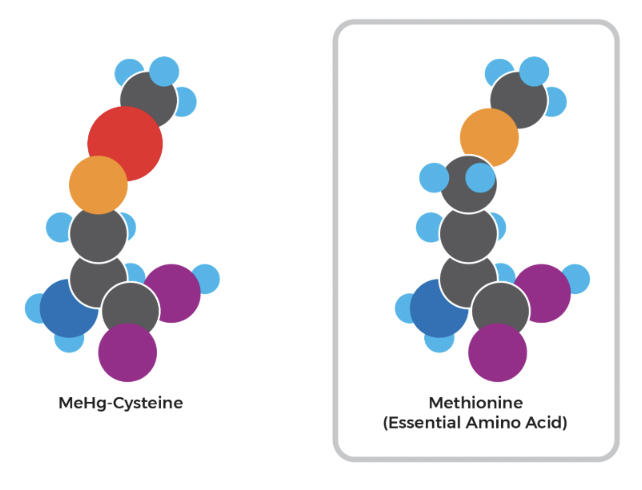

When the inhabitants of Minamata ingested methylmercury-contaminated seafood, the methylmercury was readily absorbed by their gut. Once inside the body, it binds with free-cysteine amino acids or cysteine-containing proteins. Due to structural similarities as shown by the diagram below, the methylmercuric-cysteinyl complex is recognized by receptors in the blood-brain barrier and the placenta as methionine, another amino acid, thereby allowing the complex to pass or enter both regions. This characteristic is what gives methylmercury the ability to cause cognitive issues in victims of Minamata disease. It also gives rise to congenital Minamata Disease: children who have been infected in the womb (as a result of methylmercury making it into the placenta) are born with deformed limbs, intellectual disabilities, impaired coordination, and various other complications (Yorifuji and Tsuda, 2014).

By 1959, the mercury had contaminated Minamata Bay and other parts of the Shiranui Sea. Villages up and down the sea coast began to experience the disease.

It wasn’t until 1968 – 12 years after the first cases and deaths of Minamata disease – that the Chisso factory transitioned away from producing acetaldehyde with a mercury catalyst.

Since 1959, Chisso has made numerous “sympathy money” payouts to those affected by the disease. Many of these payouts aimed to incentivize families to drop their lawsuits against Chisso. In March of 1973, the Japanese government ordered Chisso to make one-time payments of $66,000 for each deceased patient and $59,000 to $66,000 for each surviving patient.

As of 2001, over 2,000 people have been officially recognized as patients of the disease. As many as 10,000 people have received financial compensation but have yet to be recognized. To limit the liability and economic burden on Chisso, committees were formed to identify these patients who stuck to a rigid interpretation of Minamata disease. Thus, many victims could not get official patient status, resulting in many protests. Being officially recognized meant receiving financial reparations that covered the cost of medical expenses, as well as a monthly allowance (Justin McCurry, 2006).

Given that most survivors of Minamata disease are either deceased or in their final years of life, we must continue to remember and acknowledge the environmental injustices – and years of resulting suffering – perpetrated by the Chisso corporation onto the people of Minamata.

References

Chang, L. W., & Grace Liejun Guo. (1998). Chapter 29 - fetal minamata disease: Congenital methylmercury poisoning (W. Slikker & L.

W. Chang, Eds.; pp. 507–515). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012648860-9.50038-8

McCurry, J. (2006). Japan remembers Minamata. The Lancet, 367(9505), 99–100.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(06)67944-0

Methylmercury. (2024, February 10). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Methylmercury#Human_health_effects

Minamata disease. (2023, December 30). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minamata_disease#1908%E2%80%931955

Sokol, J. (2018, July 3). Something in the Water: Life after Mercury Poisoning. JSTOR Daily.

https://daily.jstor.org/life-after-mercury-poisoning/

Technology, I. E. (n.d.). Minamata Bay: The Fatal Difference Between Mercury and Methylmercury. Envirotech Online. Retrieved

February 6, 2024, from https://www.envirotech-online.com/news/environmental-laboratory/7/international-environmental-

technology/minamata-bay-the-fatal-difference-between-mercury-and-

methylmercury/60208#:~:text=The%20Minamata%20Bay%20Disaster&text=Bacteria%20in%20the%20bay

Yorifuji, T., & Tsuda, T. (2014, January 1). Minamata (P. Wexler, Ed.). ScienceDirect; Academic Press.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/B9780123864543000385